On September 11, 2001, the world watched in horror as commercial jetliners, flown by terrorists at the direction of their Al Qaeda handlers, slammed two Boeing 767s into the World Trade Center towers in Lower Manhattan. The terrorists continued their assault on the United States homeland by overtaking two more aircraft, one crashing and penetrating the Pentagon. The other marked the moment that Americans, in unity, began to fight back. During the hijacking of United Airlines Flight 93, the passengers overtook the hijackers and crashed their aircraft into a rural Pennsylvania field. At 8:30 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time, President George W. Bush addressed the world for the first time with a desire to evoke The Steel of American Resolve (U.S. State Department; Ebitz; American Broadcast Corporation; Bush). The President’s central appeal was to unify the broken and battered people of the United States, and through the strategic deployment of rhetorical strategies, he was successful.

Bush Was Successful in His Call for Unity following the September 11th Attacks

For three minutes and thirty-eight seconds, viewers watched the President’s prime-time televised address broadcast to the world. The President made his case for unity, American resolve, and action from behind what is arguably the most powerful desk in the world. Evidence supporting the President’s appeal and goal can achieved through his spoken and written words: “This is a day when all Americans from every walk of life unite [emphasis added] in our resolve for justice and peace” (Bush, 2001). In a somber tone, he spoke intentionally and deliberately to his world audience (ABC, 2001, 0:15). Through his purposely slow and precise intonation, he only stumbled upon one word (ABC, 2001, 0:37), a habit which the President had been well-known for (Warran, 2001).

Within the context of his appeal, the President used the unique word act, nine total times in three minutes and thirty-eight seconds, second only to the word America (ABC News, 2001). The President conveyed a powerful yet subtle message through his chosen prose. He called all Americans to act. Through the context of the President’s message, the President revealed the overarching theme of unity. He compelled his audience to act together in unity as Americans. The President’s subtle prose is quite revealing in his tactical deployment of pathos.

Through the subtleties of his prose, the President must have known that he was strategically deploying pathos to connect with the emotionality of his audience. The President appeared almost depleted. His eyes were heavy; he did not have the trademark side smirk of the President we most typically knew (ABC News, 2001 0:05). The President appeared somber. His eyes were direct, facing the camera, piercing its lens, connecting deeply with his audience. Examining his use of emotionality and his connectedness to his audience cannot be demonstrated more clearly than by reflecting upon the video and text together, side by side. When deploying close captioning, one quickly notices a specific pattern through which the President was connecting:

Good evening. Today, our [emphasis added] fellow citizens, our [emphasis added] way of life, our [emphasis added] very freedom came under attack in a series of deliberate and deadly terrorist acts (Bush; ABC News).

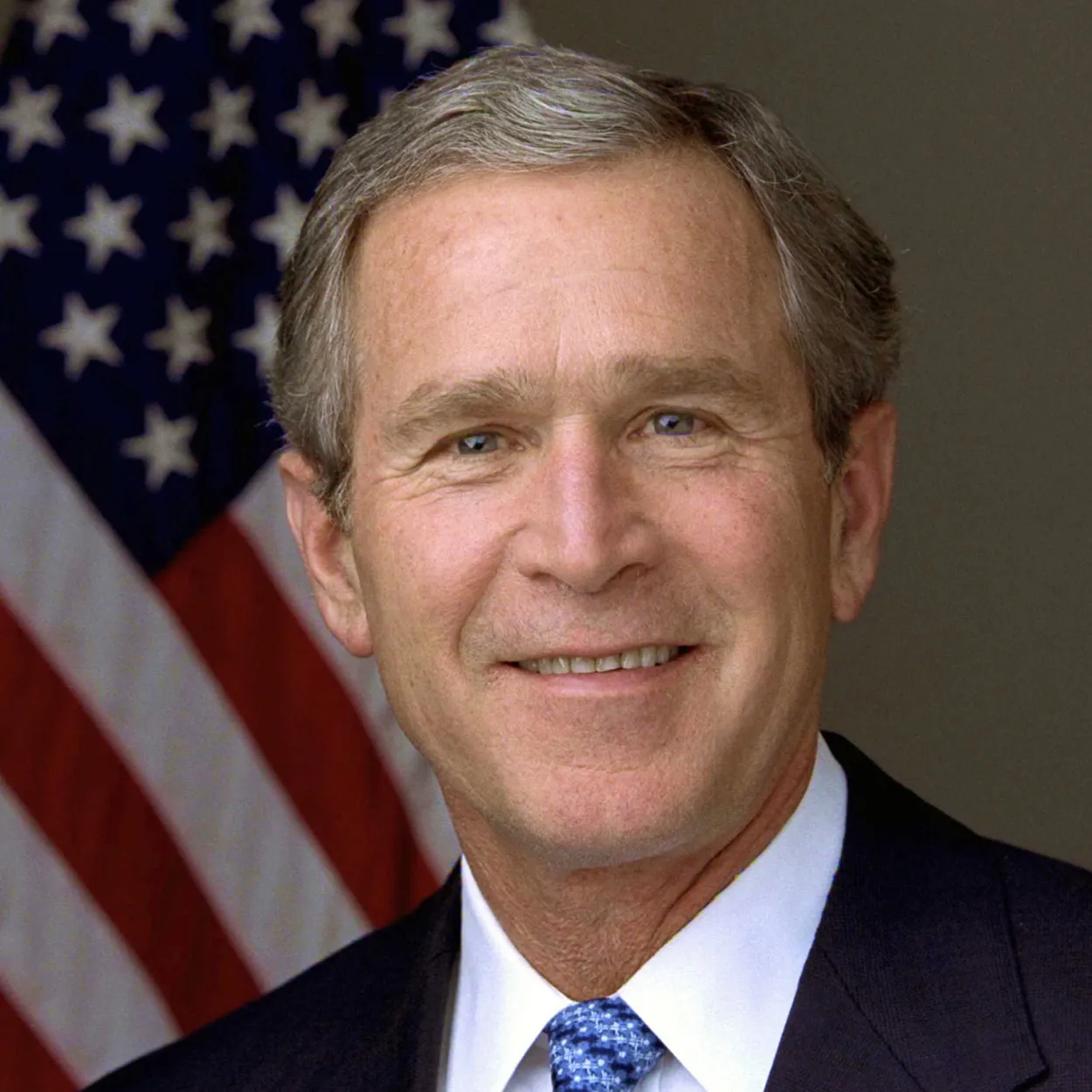

President George W. Bush

Following each occurrence of the word our, the President physically opens his hands, unclasping them and almost offering them to his audience, connecting with them. Pathos was a considerable strategy that was certainly considered by the President and his advisors when crafting his speech. Connecting emotionally with his audience served to support his overarching call for unity. Further evidence of the President’s loaded use of pathos was his emotional connection to overarching, Christian-based ideological beliefs, such as those contained within Psalm 23.1. The idea that his audience was walking through a valley overshadowed by death was quite apparent.

Yet, the President’s connectedness to the biblical theme joined him more deeply with his dominant audience members: the people of The United States of America. Christianity is the most popular religion practiced in North America, the primary location of his audience members (Mapped: The World s Major Religions, 2022).

The President levered additional emotional connectivity through the Christian overtones of protection from evil at a time of great evil in his eyes and well balanced with his overall goal of unity.

The President must have also known he had another Aristotelian strategy available for deployment. The President was the commander in chief, leader of the world’s largest democracy, and perhaps the world’s most powerful and influential person. The American people elected him, and he commanded the country from the Oval Office of the White House on September 11, 2001. His credibility was supreme; he was his audience’s ultimate authority on the day’s events. The President was the highest authority to make a statement on the day’s events, specifically elected to his office by the primary audience he spoke to. He projected his message from arguably the most powerful office in the world. For those reasons, ethos was his minority partner in his rhetorical strategy to achieve his goal of unity.

While the President connected with his audience through emotionality (pathos) and commanded authority simultaneously (ethos), he also interwove a tactical purpose, uniting his audience in pursuing a common goal. He materialized his desire to unify his audience around a common goal through his rhetoric: “This is a day when all Americans from every walk of life unite in our resolve for justice and peace. America has stood down enemies before, and we will do so this time,” (Bush, 2001, p. 1). He built an argument for the War on Terror that exists to some degree even today, and in one decisive moment he synthesized his appeal. It completed the Aristotelian Triadic thought, the full circle of his rhetoric. The President deployed effectively and powerfully logos.

The following day, the Washington Post carried the headline Bush Vows Retaliation. Chicago Tribune writer James Warran published his analysis of the Presidential Statement, aptly entitled, President’s address somber, if not stirring. Short speech delivers basics, sorrow, and threat (Warran, 2001).

Cumulatively, the President’s approval rating increased between 35 and 40 points following September 11, 2001. In the wake of the attacks, his approval rating climbed as high as 90% in what has been coined as a rally around the flag phenomena (Schubert et al., 2002).

The President endeavored to communicate a message of unity supported by effective rhetorical strategies. He communicated with the power and credibility of the Office of the President of the United States of America and did so with goodwill, good character, and authority. He communicated a common goal, one with logic and sound reasoning, a goal based on his audience’s values and precedents. The President strategically used a second Aristotelian appeal, logos, to reinforce his persuasive communication goals. In addition, the President’s appeal to duty, patriotism, and the honor of his audience aligned with their fear and overwhelmingly connected with their emotions.

He was highly influential, based on the research conducted following his speech and studied by Schubert et al., so much so that the United States would eventually unify in a total conflict in the Middle East known today as the Global War on Terrorism (America’s Wars and Conflicts, 2023). In the wake of tragedy, the President stood tall, yet battered, not unlike the people he was chosen to lead, and delivered a highly influential speech with the goal of unity. After carefully considering and evaluating his goals and means of attaining them, the President of the United States of America achieved his goal in perhaps the country’s darkest hour. He united a nation and ignited The Steel of American Resolve.

References

American Broadcast Corporation, ABC News. (2001, September 11). Former President George W. Bush addresses the nation. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gz7S1v1k664

America’s Wars and Conflicts. (2023, 09 17). Retrieved from Soldiers Walk Memorial Park: https://www.soldierswalkmemorialpark.com/americas-wars-conflicts.html

Bush, G. W. (2001, 9 11). Statement by the President in His Address to the Nation. Retrieved from The White House – President George W. Bush: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2001/09/20010911-16.html

Ebitz, C. C. (2021, 09 10). 20th Anniversary of 9/11. Retrieved 08 30, 2023, from Marine Corps Air Station New River.

Mapped: The World s Major Religions. (2022, 09 17). Retrieved from Visual Capitalist: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/mapped-major-religions-of-the-world/#:~:text=the%20world%20is.-,Christianity,Christian%20population%20of%20253%20million.

Schubert, J. N., Stewart, P. A., & Curran, M. A. (2002). A Defining Presidential Moment: 9/11 and the Rally Effect. Special Issue: 9/11 and Its Aftermath: Perspectives from Political Psychology, 559-583. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3792592

September 11, 2001: Former President George W. Bush addresses the nation. (2001). Retrieved 09 17, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gz7S1v1k664

Statista Research Department. (2022, 11 7). Deadliest terrorist attacks worldwide from 1970 to 2020, by number of fatalities and perpetrator. Retrieved from Statista: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1330395/deadliest-terrorist-attacks-worldwide-fatalities/

U.S. State Department. (2022, 10 08). A Day of Remembrance. Retrieved 08 30, 2023, from U.S. Embassy in Georgia: https://ge.usembassy.gov/a-day-of-remembrance/

Warran, J. (2001, 09 12). President’s address somber if not stirring. Short speech delivers basics, sorrow, threat. The Chicago Tribune. Chicago. Retrieved 08 30, 2023, from https://www.chicagotribune.com/chi-0109120168sep12-story.html

1 Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I fear no evil, for You are with me. King James Version, 1604, as cited in Bush, 2001. (George W. Bush, 2001)